Recently, I posted a little poem by Ogden Nash on my Facebook page.

Seeing this, one of my friends asked me about the health benefits of celery and whether it makes any difference if you eat it raw or cooked.

So here are some answers to these questions.

But first some celery background and a story of seduction.

Botany and history

Celery (Apium graveolens L.) is a member of the same botanical family as carrots, parsley and fennel – the Umbelliferae.

Modern celery originated from wild celery, native to the Mediterranean, where its seeds were once widely used as a medicine (1). It was not cultivated as a food plant until 1623.

Wild celery was mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey in about 850 BCE (2).

Odysseus and his companions were on their way to their beloved Ithaca, but Poseidon, the moody god of the seas, became angry with the hero. So he sank all the ships of Odysseus and drowned his companions.

Shipwrecked, Odysseus was tortured for nine days and nights, until the waves took him to a beautiful island called Ogygia, believed to be in Western Europe.

There he was seduced by a nymph called Calypso, who fell in love with him and would not allow him to leave.

Eventually, after seven years, Zeus – King of the gods – sent his messenger Hermes to tell Calypso to let Odysseus go.

So Hermes travelled over the endless breakers, until he reached the distant isle, then leaving the violet sea he crossed the land, and came to the vast cave where the nymph of the lovely tresses lived, and found her at home.

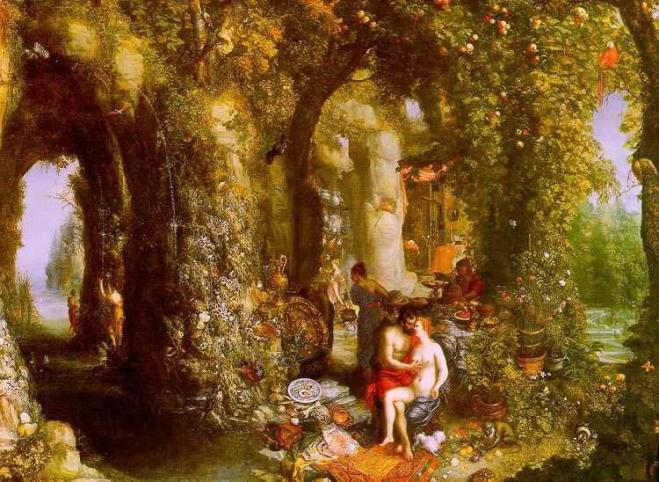

A great fire blazed on the hearth, and the scent of burning cedar logs and juniper spread far across the isle. Sweet-voiced Calypso was singing within, moving to and fro at her loom, weaving with a golden shuttle. Around the cave grew a thick copse of alder, poplar and fragrant cypress, where large birds nested, owls, and falcons, and long-necked cormorants whose business is with the sea. And heavy with clustered grapes a mature cultivated vine went trailing across the hollow entrance. And four neighbouring springs, channelled this way and that, flowed with crystal water, and all around in soft meadows iris and wild celery flourished.

Celery was considered an aphrodisiac by the Ancient Greeks and Romans (3).

Some have speculated that Calypso was rendered ravenous by her celery-rich diet and pounced on Odysseus, detaining him for years of amorous activity.

Is there any scientific evidence to support the use of celery as an aphrodisiac?

More on that later.

There is however no doubt that, for whatever reason, celery was highly prized in ancient times and its leaves were used as garlands for the winners at the Isthmian and Nemean games.

In both Ancient Greece and Ancient Egypt, celery leaves were also used as garlands for the dead. Dried inflorescences and leaves of celery were reportedly found in the tomb of Tutankhamun (4).

But back to the story…

Calypso was not best pleased when Hermes explained his mission. She ranted and raved and accused him of jealousy.

Realising, however, that it was futile to argue with Zeus, Calypso sorrowfully followed the order.

She gave Odysseus enough tools to build a solid raft.

Odysseus loaded the raft with plenty of water and food and finally made his farewells to embark on a world of new adventures.

Health benefits of celery

So what can celery do for you?

My friend said he thought celery was a pointless food – nothing but water, which takes more energy to digest than it provides.

How true is this perception?

Nutritional content of celery

Well it is true that celery contains a lot of water – 95 per cent water to be precise.

Celery is also, however, rich in vitamin C and fibre. It is a very good source of potassium, folic acid and vitamins B6 and B1; and a good source of calcium and vitamin B2 (5).

Whilst celery does contain more sodium than other vegetables, this is offset by very high levels of potassium.

One 8-inch (20 cm) celery stalk contains approximately 32 milligrams of sodium and 104 milligrams of potassium, whilst providing only 6 calories as carbohydrate (5).

This reminds me to address one common question about celery.

Is it true that you burn more calories eating celery than it provides?

A search of the internet uncovers all manner of speculation on this subject but very little scientific evidence to support it.

What we do know from science is that approximately 10 per cent of the calories we consume each day are used up in the process of eating and digesting food.

This energy ‘waste’ is called the thermogenic effect of food, dietary-induced thermogenesis, the ‘specific heat of feeding’, or the thermic effect of food.

All this means is that every time we eat, some of the calories contained in the food are lost as heat.

The exact amount of heat lost during eating can be measured by putting someone in a whole body calorimeter, giving them food to eat, and recording the change in temperature.

To my knowledge, nobody has actually measured a person’s heat production after eating a meal of celery alone, so we are left to guess what might happen from the results of other experiments.

Measurements show that some foods are digested with little heat loss, for example, fat-based foods.

High protein foods are the opposite and generate a lot of heat – presumably because the body has to work harder to digest protein.

Celery consists of mostly water and fibre. So what is the thermogenic effect of water and fibre?

Almost nothing.

In fact, if you put someone in a whole body calorimeter and give them a high-fibre diet, their post-food heat production is actually reduced compared to a normal diet (6)(7)(8).

Supplementing a balanced 240 kcal meal with 3 grams of fibre (equivalent of five celery stalks) reduces the overall thermogenic effect of the meal by 19 kcal. This effectively means that of the 30 calories gained from eating your celery stalks, 19 calories fewer are used processing it than if it did not have the fibre in it.

So, after being chewed, the fibre in celery gets passed through the gut and out the other end without the body doing too much to it on the way. Although it may take you a while to chew the celery stalks, the gut does not waste much time on it.

So, sorry dieters, but it is unlikely that eating celery burns more calories than it provides.

You could go for a walk whilst munching celery; that would work.

For those of you who like geeky information, here is a detailed breakdown of the nutrients in raw celery.

| Nutrient | Unit | Value per 100 g |

| Water | g | 95.43 |

| Energy | kcal | 16 |

| Protein | g | 0.69 |

| Total lipid (fat) | g | 0.17 |

| Carbohydrate, by difference | g | 2.97 |

| Fibre, total dietary | g | 1.6 |

| Sugars, total | g | 1.83 |

| Minerals | ||

| Calcium, Ca | mg | 40 |

| Iron, Fe | mg | 0.2 |

| Magnesium, Mg | mg | 11 |

| Phosphorus, P | mg | 24 |

| Potassium, K | mg | 260 |

| Sodium, Na | mg | 80 |

| Zinc, Zn | mg | 0.13 |

| Vitamins | ||

| Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid | mg | 3.1 |

| Thiamin | mg | 0.021 |

| Riboflavin | mg | 0.057 |

| Niacin | mg | 0.32 |

| Vitamin B-6 | mg | 0.074 |

| Folate, DFE | µg | 36 |

| Vitamin B-12 | µg | 0 |

| Vitamin A, RAE | µg | 22 |

| Vitamin A, IU | IU | 449 |

| Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) | mg | 0.27 |

| Vitamin D (D2 + D3) | µg | 0 |

| Vitamin D | IU | 0 |

| Vitamin K (phylloquinone) | µg | 29.3 |

| Lipids | ||

| Fatty acids, total saturated | g | 0.042 |

| Fatty acids, total monounsaturated | g | 0.032 |

| Fatty acids, total polyunsaturated | g | 0.079 |

| Cholesterol | mg | 0 |

Phytochemical content

In addition to the nutrients listed above, celery contains literally hundreds of powerful phytochemicals (9).

Celery seeds contain 1.5 to 3 per cent volatile oil responsible for the characteristic aroma of celery. The chemical constituent of celery seed volatile oil was found to be 60–70 per cent limonene, phthalides and β-salinene, coumarins, furanocoumarins (bergapten) and flavonoids (apiin, apigenin).

Some of the phytochemicals identified in celery are listed below (10).

|

Compound

|

Percentage

|

|

Limonene

|

72.16

|

|

beta-Selinene

|

12.17

|

|

n-butyl phthalide

|

2.56

|

|

Lingustilide

|

2.41

|

|

alpha-Selinene

|

2.05

|

|

Linalool

|

1.48

|

|

alpha-Pinene

|

1.05

|

|

Myrcene

|

0.95

|

|

Sabenene

|

0.76

|

|

r-Cymene

|

0.74

|

|

Epoxycaryophyllene

|

0.55

|

|

Eudesmol

|

0.29

|

|

Caryophyllene

|

0.17

|

|

Thymol

|

0.17

|

|

Isopulegone

|

0.16

|

|

Cinnamic aldehyde

|

0.15

|

|

Carvone

|

0.09

|

|

alpha-lonone

|

0.05

|

|

Geranyl acetate

|

0.04

|

|

beta-Phellandrene

|

0.02

|

|

Pentyl benzene

|

0.02

|

|

Camphene

|

Traces

|

|

beta-Pinene

|

Traces

|

|

3-carene

|

Traces

|

|

alpha-Phellandrene

|

Traces

|

|

(Cis) beta-Ocimene

|

Traces

|

|

(Trans)beta-Ocimene

|

Traces

|

Use as a herbal medicine

Traditionally, wild celery was used as an herbal medicine with a range of alleged properties (11) (12), including:

- Aphrodisiac

- Anthelmintic

- Anti-inflammatory, for rheumatic conditions

- Antiseptic, especially for urinary tract infections

- Antispasmodic,

- Carminative – prevents formation of gas in the gastrointestinal tract or facilitates the expulsion of said gas, thereby combating flatulence

- Diuretic

- Emmenagogue, stimulates blood flow in the pelvic area and uterus

- Laxative

- Sedative

- Stimulant

- Tonic

Modern scientific studies have revealed that many of the phytochemicals found in celery and other plants possess interesting biological activity (13).

It is important to note that most studies to date have used animal models and effects in humans have yet to be proven.

That said, there is some interesting evidence developing for various potential health benefits of celery.

Scientific evidence for health benefits of celery

Anti-hypertensive – lowers blood pressure

In animal studies, extracts of celery have been shown to reduce blood pressure (14, 15).

The flavone apigenin and the isobenzofuranone, 3-n-butylphthalide, are two of the phytochemicals best studied in this respect.

In one experiment, a very small amount of 3-n-butylphthalide, equivalent to that in four stalks of celery, lowered blood pressure by 12 to 14 per cent (16).

In animals, 3-n-butylphthalide appears to lower blood pressure by acting as both a diuretic and vasodilator (causes the blood vessels to expand) by influencing the production of hormone-like substances called prostaglandins, as well as acting in a similar manner to calcium-channel blockers (17).

Apigenin has also been shown to affect vasodilation by stimulating calcium channels in rat cell membranes (18).

Hypolipidemic – lowers cholesterol and triglycerides

3-n-butylphthalate has also been shown to lower blood cholesterol levels and reduce the formation of arterial plaque in preclinical studies (animal and in vitro studies) (19) (20).

This effect may increase the elasticity of blood vessels and also lead to lower blood pressure readings.

3-n-butylphthalate also appears to promote some effects on areas and systems of the brain that control vascular resistance (21).

Other studies in rats show that extracts of celery, containing terpenoid, tannin, alkaloid, glycoside, flavonoid and sterol phytochemicals, dose dependently inhibited total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low density lipoprotein levels, and significantly increased high density lipoprotein level (22).

Anti-inflammatory – reduces inflammation

Extracts of celery have been investigated and found to have significant anti-inflammatory activity in animal models (23) (24).

It is proposed that the anti-inflammatory activity of celery may form a basis for the reputation of the plant as a medicinal treatment for rheumatic and arthritic diseases.

Flavonoids are reported to affect the inflammatory process and to possess anti-inflammatory as well as immunomodulatory activity in vitro and in vivo.

Since nitric oxide produced by inducible nitric oxide synthase is one of the inflammatory mediators, the effects of celery extracts containing the flavonoid apiin as a major constituent, on inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide production were evaluated in a cell line (25).

The extract, and apiin alone, showed significant inhibitory activity on nitrite (NO) production.

Further tests on mice showed that the extract exerted anti-inflammatory activity in vivo, with a potency seven-times lower than that of indometacin, the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug used as reference (25).

Luteolin, another flavonoid found in celery, demonstrates a spectrum of biological activities.

Some Chinese researchers looked at the anti-inflammatory activity of luteolin in acute and chronic models in mice. They observed suppression of inflammation in vivo (26).

Further experiments provided evidence that luteolin may be a potent selective inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), which is the same target as that of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (26).

Anti-cancer

Many of the phytochemicals in celery are the subject of research for their potential anti-cancer activities (27)(28).

Luteolin, for example, is a flavonoid found in celery. It has been found to inhibit angiogenesis, induce apoptosis, prevent carcinogenesis in animal models, reduce tumour growth in vivo and to sensitize tumour cells to the cytotoxic effects of some anticancer drugs (29)(30).

Apigenin in celery has also been shown to regulate the cell cycle and thus may have benefits for cancer prevention (31).

Extracts of celery have been found to protect against chemically induced liver cancer in animal models (32).

Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), the most abundant phthalate in the environment, is known to be a reproductive toxicant. Researchers in Egypt investigated whether celery oil affects DEHP-induced testicular toxicity. They found that celery oil partially prevented the damaging effects of this environmental toxin (33).

Antiulcerogenic – inhibits stomach ulcers

Celery oil was found to inhibit stomach ulcers in a dose-dependent manner in experimental rats, which was similar to that induced by omeprazole, a widely used drug for indigestion, acid reflux and peptic ulcers (34). The major phyochemicals identified were β-pinene, camphene, cumene, limonene, α-thuyene, α-pinene, β-phellendrene, p-cymene, γ-terpinene, sabinene and terpinolene.

In another study with rats, pretreatment with celery extract produced dose-dependent reduction in all experimentally induced gastric lesions, with no toxic side effects or mortality over a period of 14 days. The phytochemical screening showed the presence of flavonoids, tannins, volatile oils, alkaloids, sterols and/or triterpenes. The authors concluded that celery extract significantly protects the gastric mucosa and suppresses the basal gastric secretion in rats, possibly through its antioxidant potential (35).

Anti-oxidant activity

Dietary plants contain variable chemical families and amounts of antioxidants. Celery is no exception.

Antioxidants can eliminate free radicals and other reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, and these reactive species contribute to most chronic diseases. It is hypothesized that antioxidants originating from foods may work as antioxidants in their own right in vivo, as well as bring about beneficial health effects through other mechanisms, including acting as inducers of mechanisms related to antioxidant defence, longevity, cell maintenance and DNA repair (36).

The antioxidant content of celery products compared with broccoli and blueberries is shown below (36).

It is important to note the considerable variability between samples depending on environment, cultivar and type of product.

| Product | Antioxidant content |

| mmol per 100g | |

| Celery seeds | 8.17 |

| Celery leaves, dried | 16.91 |

| Celery raw, USA | 0.06 |

| Celery raw, Mali | 0.81 |

| Celery blanched | 0 |

| Broccoli raw, Norway | 0.85 |

| Broccoli raw, USA | 0.25 |

| Broccoli raw, Spain | 0.68 |

| Blueberries, cultivated USA | 1.85 |

| Blueberries, cultivated Norway | 1.26 |

Anti-microbial activity

Celery is reported to have anti-bacterial and weak anti-fungal activity.

Celery extracts have been shown to have potent activity against Helicobacter pylori, a gram-negative bacterium found in the stomach (37). H. pylori has been associated with chronic gastritis and gastric ulcers, conditions that were not previously believed to have a microbial cause. It is also linked to the development of duodenal ulcers and stomach cancer, though 80 per cent of people infected display no disease symptoms.

Essential oil of celery has also been shown to be strongly inhibitory against Escherichia coli and moderately inhibitory against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus (34).

Moderate anti-microbial activity has been shown by extracts of celery against multi-drug resistant Salmonella typhi (38).

This anti-microbial activity may explain the use of celery as a traditional herbal remedy for urinary tract and other infections.

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is an age-related, progressive neurodegenerative disorder that occurs gradually and results in memory, behaviour, and personality changes.

L-3-n-butylphthalide, an extract from seeds of celery, has been shown to have neuroprotective effects on ischaemic, vascular dementia, and amyloid-beta-infused animal models (39).

Treatment with L-3-n-butylphthalide significantly improved the spatial learning and memory deficits of transgenic mice compared to the controls.

It is believed to do this by inhibiting oxidative injury, neuronal apoptosis and glial activation, regulating amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP) processing and reducing Aβ generation (40).

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory and demyelinating disease of the central nervous system which mainly affects young adults.

An animal model of multiple sclerosis called experimental allergic encephalomyelitis is used to test potential treatments for this disease.

In Iran, a herbal-marine product called MS14, containing 90 per cent Penaeus latisculatus (Western King prawn), 5 per cent Apium graveolens (celery), and 5 per cent Hypericum perforatum L (St John’s Wort) is used to slow down or halt the progression of multiple sclerosis.

Mice with induced brain inflammation were fed a diet containing MS14 (30 per cent) and monitored for 20 days. The disease was slowed down in the treated mice relative to the controls. Moreover, while there were moderate to severe neuropathological changes in the controls, milder changes were seen in the mice treated with MS14 (41).

The precise role of celery in this remedy has not been elucidated and a great deal more work is required to determine its value for this indication.

Aphrodisiac

Earlier I recounted the story of Calypso and Odysseus, full of desire in their celery-adorned cave.

This is not the only myth implicating celery as an aphrodisiac (42).

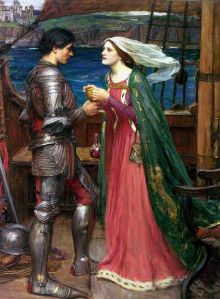

Central to the Celtic legend of Tristan and Isolde is a love potion, which they accidentally consume and are overcome with passion. This is unfortunate as Tristan is escorting Isolde on her way to marry his uncle.

Some say that their magic philtre contained celery root, though there is no direct evidence for this. Love potions were usually made from mandrake (love apples), a poisonous member of the nightshade family, with other ingredients including orange, ambergris, vervain, briony and fern seed.

In the 18th century, Grimod de la Reyniere, an early food journalist, warned of celery’s aphrodisiac properties, advising that

it is not in any way a salad for bachelors

It is rumoured that Madame de Pompadour, maverick mistress of King Louis XV, invented a celery soup to inflame the desires of her royal lover.

So is there any scientific evidence to support these claims?

In 1979, two researchers reported that they had identified the volatile steroid, 5 alpha-androst-16-en-3-one, in the cytoplasm of parsnip and celery at concentrations of 8 nanograms per gram (8 parts per billion) (43).

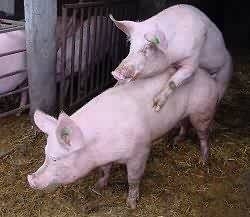

This steroid is a pheromone found in both human male and female sweat and urine. It is also found in high concentrations in the saliva of male pigs, and, when sniffed by a female pig that is in heat, results in the female assuming the mating stance. Androstenone is the active ingredient in ‘Boarmate’, a commercial product made by DuPont sold to pig farmers to test sows for timing of artificial insemination.

Androstenone was the first mammalian pheromone to be identified and has thus been the subject of considerable study.

It turns out that the ability to smell androstenone is genetically determined (44).

Some people cannot smell it at all, whilst others can detect it down to levels of 0.2 parts per billion, which is 40 times lower than the concentration of androstenone reported in celery.

The speculation is that the smell of androstenone in celery acts as an aphrodisiac in sensitive individuals, though there is no direct evidence to confirm this.

The other speculation is that the action of certain phytochemicals in celery as potent vasodilators, as described above in the section on blood pressure (17), enhances male erectile function and thus sexual potency.

Again, however, there is no direct evidence to substantiate this hypothesis and, on the whole, scientists are dismissive of claims of the aphrodisiac properties of plants (45).

This does not necessarily mean that scientists are right – this is a notoriously difficult subject to study and research funding for it is hard to obtain – so, until more data are available, you will have to conduct your own experiments…

Adverse effects of celery

Celery produces phytochemicals called psoralens, which are furanocoumarins (46).

Psoralens are believed to be phytoalexins associated with celery resistance to pathogens. High levels of psoralens are produced by celery infected with fungal pathogens.

When these compounds are exposed to long-wave UV light or sunlight the phototoxic furanocoumarins become carcinogenic agents; recognized as causally-related to skin cancer by the World Health Organization.

Photodermatitis of the fingers, hands and forearms is therefore a known occupational risk for celery handlers and field workers (47).

Workers in grocery stores and agricultural workers have also been reported to suffer skin reactions after handling celery and being exposed to UV light.

One case reported in the medical literature involved a 65-year-old woman who developed a severe, generalized phototoxic reaction following a visit to a suntan parlour. History taking revealed that she had consumed a large quantity of celery root one hour earlier.

Some people suffer allergic reactions to celery, caused by a protein called Api g 2; exposure can produce mild symptoms of skin irritation or cause potentially fatal anaphylactic shock.

Cooking celery does not destroy the proteins which cause the allergic reaction.

Allergy to celery seems to be linked to people with seasonal hay fever to birch and/or mugwort pollen (usually March/April) (47). This is called cross-reaction and is often an important cause of food allergies.

Celery allergy seems to be far more common in central Europe, mainly France, Switzerland and Germany, and less so in the UK and US, where peanut allergy is the most common.

Should you eat celery raw or cooked?

From a purely nutritional point of view, it is generally the case that storage and cooking of vegetables leads to loss of nutrients. The bioavailability of some nutrients, such as iron, may however be increased by cooking (48).

Loss of vitamins and minerals from vegetables is mainly because of extraction into the cooking liquid rather than their destruction. So provided that you consume the cooking liquid, as you do with soups and casseroles for example, you will still benefit from the nutrients.

Phytochemicals vary substantially in their stability to temperature, light and pH (49).

In general, the less food plants are processed and cooked the more phytochemicals remain active, but this is not always the case.

Spanish scientists investigated the influence of home cooking methods (boiling, microwaving, pressure-cooking, griddling, frying, and baking) on antioxidant activity in 20 vegetables (50).

Artichoke was the only vegetable that kept its very high antioxidant activity in all the cooking methods.

Highest losses of antioxidant activity were observed in cauliflower after boiling and microwaving; pea after boiling; courgette (zucchini) after boiling and frying; and swiss chard and pepper with all methods.

Beetroot, green bean, and garlic kept their antioxidant activity after most cooking treatments.

Celery reportedly increased its antioxidant capacity in all the cooking methods, except boiling when it lost 14 per cent.

Whether to eat celery raw or cooked is a matter of personal choice and depends on your preferences, your constitution, your condition at the time and your external environment.

In hot weather, raw celery is very cooling.

When the weather is cooler or if your digestive system is weak, it may be better to eat cooked celery in a soup or casserole.

Recipes with celery

Raw celery can be used in salads, as crudites to eat with vegetable dips, and as an ingredient in a refreshing green juice.

Cooked celery can be used in soups, sauces and casseroles.

Celery, cucumber, apple, parsley and lime juice

Green juices are a great way to include a wider variety of vegetables in your diet, are packed with nutrients and easy to digest.

Here is a delicious recipe for a refreshing, cooling green juice, ideal for a hot day.

Please click here for details: Recipe for celery, cucumber, apple, parsley and lime juice.

Celery, cucumber, apple, parsley and lime juice – Jane Philpott at http://www.cookingforhealth.biz

Pressed salad with celery, cucumber, fennel and radish

On the hottest days, we need to balance the external heat by using raw vegetables with cooling properties. This crunchy, tangy salad using celery is easy to prepare and ideal for al fresco meals.

Please click here for details: Recipe for celery, fennel, cucumber and radish pressed salad

Celery and sweetcorn chowder

This simple, sweet, summery soup recipe can be served warm or cold. It soothes the digestive system and helps to relax you at the start of a meal.

Please click here for details: Recipe for celery and sweetcorn chowder.

Celery and sweetcorn chowder – Jane Philpott at http://www.cookingforhealth.biz

And finally…

Given that I have just devoted a whole blog post to extolling the virtues of celery, do I think you should rush off and start buying wholesale quantities?

Of course not.

That would be silly.

Why?

The reason is that I could choose almost any food plant and write a similar article about all the wonderful nutrients and phytochemicals it contains and the beneficial effects of these substances on your health.

All plants contain an incredible array of substances with powerful biological activity, which protect our bodies from damage and help to prevent and treat chronic disease.

These substances vary from plant to plant and it is the COMBINATION of all of them, operating together in a coordinated and often synergistic manner to regulate gene expression, which results in optimum health.

So just make sure you eat as many whole plant foods as possible and you will maximise your chances of living a long and healthy life.

If you have enjoyed this post please leave your comments below.

If you would like to keep in touch, please click here to sign up for my free e-newsletter and browse my website.

You can also join me on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and LinkedIn, where I post interesting information which is not included in this blog.

References

(1) Rubatzky, V.E. and Yamaguchi, M. (1997), World Vegetables, second edition, N.Y. Chapman & Hall, pp. 432–443.

(2) Homer, the Odyssey, Book V, 71-82

(3) Domeena C. Renshaw. Aphrodisiacs: The Science and the Myth. JAMA. 1986;255(1):98-99. doi:10.1001/jama.1986.03370010108037

(4) D. Zohary and M. Hopf, Domestication of Plants in the Old World, (3rd ed. 2000) p.202.

(5) U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2012. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 25. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page, http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata

(6) Mikkelsen PB, Toubro S, & Astrup A (2000). Effect of fat-reduced diets on 24-h energy expenditure: comparisons between animal protein, vegetable protein, and carbohydrate. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 72 (5), 1135-41 PMID: 11063440

(7) Raben A, Christensen NJ, Madsen J, Holst JJ, & Astrup A (1994). Decreased postprandial thermogenesis and fat oxidation but increased fullness after a high-fiber meal compared with a low-fiber meal. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 59 (6), 1386-94 PMID: 8198065

(8) Westerterp, K. (2004). Diet induced thermogenesis Nutrition & Metabolism, 1 (1) DOI: 10.1186/1743-7075-1-5

(9) Dr Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases http://www.ars-grin.gov/duke/index.html

(10) CU JIAN-QIN, ZHONG JZ and PAR P (1990) GCMs analysis of the essential oil of celery seed. Indian Perfumer. 34(1–4), vi-vii.

(11) Grieve, M. A Modern Herbal. 1931. Jonathan Cape Ltd, London.

(12) Duke, J.A. The Green Pharmacy. Herbal remedies for common diseases and conditions. Rodale International Ltd; New edition edition (3 Jan 2003)

(13) Higdon, J. and Drake, V.J. An Evidence-based Approach to Phytochemicals and Other Dietary Factors. Linus Pauling Institute, Hardcover (2013), 2nd Edition, 368 pp. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/books.html

(14) Ma X, He D, Ru X, Chen Y, Cai Y, Bruce IC, Xia Q, Yao X, Jin J. Apigenin, a plant-derived flavone, activates transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 cation channel. Br J Pharmacol. 2012 May;166(1):349-58. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01767.x. PubMed PMID: 22049911; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3415659.

(15) Moghadam MH, Imenshahidi M, Mohajeri SA. Antihypertensive effect of celery seed on rat blood pressure in chronic administration. J Med Food. 2013 Jun;16(6):558-63. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2012.2664. Epub 2013 Jun 4. PubMed PMID: 23735001; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3684138.

(16) Le QT, Elliott WJ. Hypotensive and hypocholesterolemic effects of celery oil may be due to BuPh. Clin Res.1991;39:173A.

(17) Tsi D, Tan BKH. Cardiovascular pharmacology of 3-n-butylphthalide in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Phytotherapy Research. 1997;11:576-582.

(18) Ma X, He D, Ru X, Chen Y, Cai Y, Bruce IC, Xia Q, Yao X, Jin J. Apigenin, a plant-derived flavone, activates transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 cation channel. Br J Pharmacol. 2012 May;166(1):349-58. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01767.x. PubMed PMID: 22049911; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3415659.

(19) Le QT, Elliott WJ. Dose-response relationship of blood pressure and serum cholesterol to 3-n-butylphthalide, a component of celery oil. Clin Res. 1991;39:750A.

(20) Mimura Y, Kobayashi S, Naitoh T, Kimura I, Kimura M. The structure-activity relationship between synthetic butylidenephthalide derivatives regarding the competence and progression of inhibition in primary cultures proliferation of mouse aorta smooth muscle cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995;18(9):1203-1206.

(21) Yu SR, Gao NN, Li LL, Wang ZY, Chen Y, Wang WN. The protective effect of 3-butyl phthalide on rat brain cells. Yao Hsueh Hsueh Pao. 1988;23(9):656-661.

(22) Iyer D, Patil UK. Effect of chloroform and aqueous basic fraction of ethanolic extract from Apium graveolens L. in experimentally-induced hyperlipidemia in rats. J Complement Integr Med. 2011 Sep 27;8. doi:pii: /j/jcim.2011.8.issue-1/1553-3840.1529/1553-3840.1529.xml. 10.2202/1553-3840.1529. PubMed PMID: 22718672.

(23) Lewis, D.A.; Tharib, S.M.; Bryan, G.; Veitch, A. Pharmaceutical Biology, 1985, Vol. 23, No. 1 : Pages 27-32. The Anti-inflammatory Activity of Celery Apium graveolens L. (Fam. Umbelliferae) (doi: 10.3109/13880208509070685)

(24) Al-Hindawi MK, Al-Deen IH, Nabi MH, Ismail MA. Anti-inflammatory activity of some Iraqi plants using intact rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1989 Sep;26(2):163-8. PubMed PMID: 2601356.

(25) Mencherini T, Cau A, Bianco G, Della Loggia R, Aquino RP, Autore G. An extract of Apium graveolens var. dulce leaves: structure of the major constituent, apiin, and its anti-inflammatory properties. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2007 Jun;59(6):891-7. PubMed PMID: 17637182.

(26) Ziyan L, Yongmei Z, Nan Z, Ning T, Baolin L. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activity of luteolin in experimental animal models.Planta Med. 2007 Mar;73(3):221-6. Epub 2007 Mar 12. PubMed PMID: 17354164.

(27) Christensen LP, Brandt K. Bioactive polyacetylenes in food plants of the Apiaceae family: occurrence, bioactivity and analysis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006 Jun 7;41(3):683-93. Epub 2006 Mar 7. Review. PubMed PMID: 16520011.

(28) Ren S, Lien EJ. Natural products and their derivatives as cancer chemopreventive agents. Prog Drug Res. 1997;48:147-71. Review. PubMed PMID: 9204686.

(29) López-Lázaro M. Distribution and biological activities of the flavonoid luteolin. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009 Jan;9(1):31-59. Review. PubMed PMID: 19149659.

(30) Lim do Y, Jeong Y, Tyner AL, Park JH. Induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HT-29 human colon cancer cells by the dietary compound luteolin. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007 Jan;292(1):G66-75. Epub 2006 Aug 10. PubMed PMID: 16901994.

(31) Meeran SM, Katiyar SK. Cell cycle control as a basis for cancer chemoprevention through dietary agents. Front Biosci. 2008 Jan 1;13:2191-202. Review. PubMed PMID: 17981702; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2387048.

(32) Sultana S, Ahmed S, Jahangir T, Sharma S. Inhibitory effect of celery seeds extract on chemically induced hepatocarcinogenesis: modulation of cell proliferation, metabolism and altered hepatic foci development. Cancer Lett. 2005 Apr 18;221(1):11-20. PubMed PMID: 15797622.

(33) Madkour NK. The beneficial role of celery oil in lowering of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-induced testicular damage. Toxicol Ind Health. 2012 Nov 16. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 23160384.

(34) Baananou S, Bouftira I, Mahmoud A, Boukef K, Marongiu B, Boughattas NA. Antiulcerogenic and antibacterial activities of Apium graveolens essential oil and extract. Nat Prod Res. 2013 Jun;27(12):1075-83. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2012.717284. Epub 2012 Aug 30. PubMed PMID: 22934666.

(35) Al-Howiriny T, Alsheikh A, Alqasoumi S, Al-Yahya M, ElTahir K, Rafatullah S. Gastric antiulcer, antisecretory and cytoprotective properties of celery (Apium graveolens) in rats. Pharm Biol. 2010 Jul;48(7):786-93. doi: 10.3109/13880200903280026. PubMed PMID: 20645778.

(36) Carlsen MH, Halvorsen BL, Holte K, Bøhn SK, Dragland S, Sampson L, Willey C, Senoo H, Umezono Y, Sanada C, Barikmo I, Berhe N, Willett WC, Phillips KM, Jacobs DR Jr, Blomhoff R. The total antioxidant content of more than 3100 foods, beverages, spices, herbs and supplements used worldwide. Nutr J. 2010 Jan 22;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-3. PubMed PMID: 20096093; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2841576.

(37) Zhou Y, Taylor B, Smith TJ, Liu ZP, Clench M, Davies NW, Rainsford KD. A novel compound from celery seed with a bactericidal effect against Helicobacter pylori. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009 Aug;61(8):1067-77. doi: 10.1211/jpp/61.08.0011. PubMed PMID: 19703351.

(38) Rani P, Khullar N. Antimicrobial evaluation of some medicinal plants for their anti-enteric potential against multi-drug resistant Salmonella typhi. Phytother Res. 2004 Aug;18(8):670-3. PubMed PMID: 15476301.

(39) Peng Y, Sun J, Hon S, Nylander AN, Xia W, Feng Y, Wang X, Lemere CA. L-3-n-butylphthalide improves cognitive impairment and reduces amyloid-beta in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2010 Jun 16;30(24):8180-9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0340-10.2010. PubMed PMID: 20554868.

(40) Peng Y, Hu Y, Xu S, Li P, Li J, Lu L, Yang H, Feng N, Wang L, Wang X. L-3-n-butylphthalide reduces tau phosphorylation and improves cognitive deficits in AβPP/PS1-Alzheimer’s transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29(2):379-91. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111577. PubMed PMID: 22233765.

(41) Tafreshi AP, Ahmadi A, Ghaffarpur M, Mostafavi H, Rezaeizadeh H, Minaie B, Faghihzadeh S, Naseri M. An Iranian herbal-marine medicine, MS14, ameliorates experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Phytother Res. 2008 Aug;22(8):1083-6. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2459. PubMed PMID: 18570265.

(42) Mark Douglas Hill. The Aphrodisiac Encycopedia – a compendium of culinary come-ons. Square Peg, 6 October 2011.

(43) Claus R, Hoppen HO. The boar-pheromone steroid identified in vegetables. Experientia. 1979 Dec 15;35(12):1674-5. PubMed PMID: 520500.

(44) Wysocki CJ, Beauchamp GK. Ability to smell androstenone is genetically determined. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Aug;81(15):4899-902. PubMed PMID: 6589634; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC391599.

(45) Domeena C. Renshaw, MD. Aphrodisiacs: The Science and the Myth JAMA. 1986;255(1):98-99. doi:10.1001/jama.1986.03370010108037

(46) Alan Crozier, Michael N. Clifford, Hiroshi Ashihara (Editors). Plant Secondary Metabolites: Occurrence, Structure and Role in the Human Diet. Wiley Online Library. Published Online: 12 NOV 2007; Print ISBN: 9781405125093; Online ISBN: 9780470988558; DOI: 10.1002/9780470988558

(47) Deleo VA. Photocontact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17(4):279-88. Review. PubMed PMID: 15327473.

(48) Gadermaier G, Hauser M, Egger M, Ferrara R, Briza P, Santos KS, Zennaro D, Girbl T, Zuidmeer-Jongejan L, Mari A, Ferreira F. Sensitization prevalence, antibody cross-reactivity and immunogenic peptide profile of Api g 2, the non-specific lipid transfer protein 1 of celery. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e24150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024150. Epub 2011 Aug 29. PubMed PMID: 21897872; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3163685.

(49) Brijesh K. Tiwari (Editor), Nigel P. Brunton (Editor), Charles Brennan (Editor). Handbook of Plant Food Phytochemicals: Sources, Stability and Extraction [Hardcover]. Wiley-Blackwell (22 Feb 2013)

(50) Jiménez-Monreal AM, García-Diz L, Martínez-Tomé M, Mariscal M, Murcia MA. Influence of cooking methods on antioxidant activity of vegetables. J Food Sci. 2009 Apr;74(3):H97-H103. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01091.x. PubMed PMID: 19397724.

In 1976, the Royal College of Physicians and the British Cardiac Society in a report on heart disease, recommended eating less fatty red meat and more poultry instead because it was lean. However, the situation has changed since then.

In 1976, the Royal College of Physicians and the British Cardiac Society in a report on heart disease, recommended eating less fatty red meat and more poultry instead because it was lean. However, the situation has changed since then.