It’s not uncommon to read newspaper headlines about nutrient deficiencies from vegetarian or vegan diets – people love good news about their bad habits.

When you scratch beneath the surface of such headlines, though, it usually becomes obvious that the individual concerned wasn’t eating enough food in general or was suffering from another health condition.

Nevertheless, vitamin B12 deficiency is often quoted as a reason for avoiding plant-based or vegan diets.

Plant-based dishes by Jane Philpott at http://www.cookingforhealth.biz

So is this justified?

Please read on if you’re interested in finding out.

What is vitamin B12 and why do you need it?

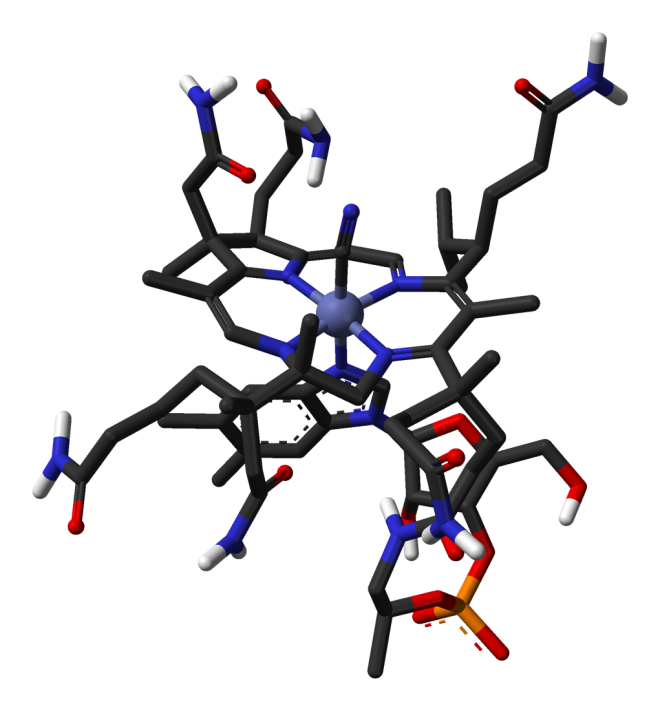

Vitamin B12, also called cobalamin, is a cobalt-containing water-soluble B vitamin.

It’s one of eight B vitamins, all of which help the body convert food (carbohydrates) into fuel (glucose), which is used to produce energy.

These B vitamins, often referred to as B complex vitamins, also help the body use fats and protein. B complex vitamins are needed for healthy skin, hair, eyes, and liver. They also help the nervous system function properly.

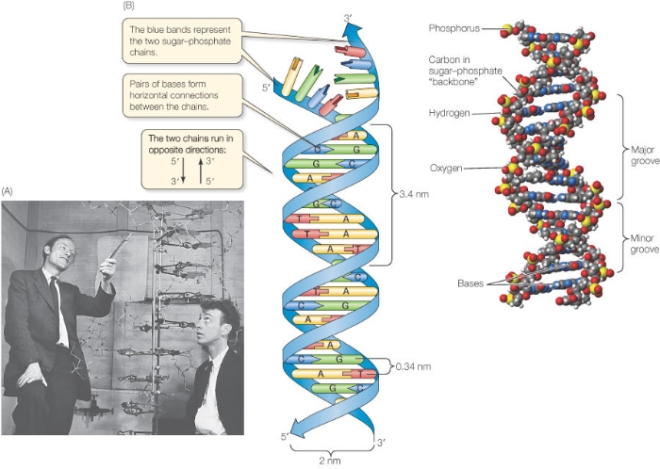

Vitamin B12 is an especially important vitamin for maintaining healthy nerve cells, and it helps in the production of DNA and RNA, the body’s genetic material.

Vitamin B12 also works closely with vitamin B9, also called folate or folic acid, to help make red blood cells and to help iron work better in the body.

Folate and B12 work together to produce S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), a compound involved in immune function and mood.

Vitamins B12, B6, and B9 work together to control blood levels of the amino acid homocysteine. High levels of homocysteine are associated with a number of chronic health conditions, including heart disease, dementia and multiple sclerosis. Researchers aren’t sure whether homocysteine is a cause of these conditions or just a marker that indicates someone may have such a condition.

Vitamin B12, or cobalamin, belongs to a family of closely related chemicals, called corrinoids, some of which are biologically inactive in humans. The inactive versions are sometimes referred to as pseudovitamin B12 (1).

The two vitamin B12 coenzymes known to be metabolically active in mammalian tissues are 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin.

How much vitamin B12 do you need?

Dietary guidelines for intake of vitamin B12 vary from country to country.

In the US, Australia and New Zealand the guideline is 2.4 µg (micrograms) per day; in the UK it’s 1.5 µg per day; and in the EU it’s 1 µg per day.

On average the guideline is about 2 µg (micrograms) per day for adults and <1 µg per day for children.

One microgram is one-millionth of a gram, so only trace amounts of this vitamin are required.

What happens if you don’t consume enough vitamin B12?

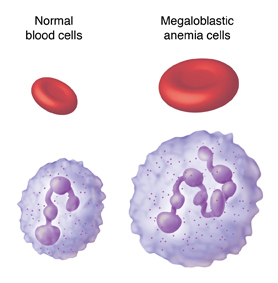

Symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency include a type of anaemia, called megaloblastic or macrocystic anaemia, which results from inhibition of DNA synthesis during production of red blood cells. The red blood cells grow larger than normal and are less able to carry oxygen.

Megaloblastic anaemia is fatal if untreated, but can usually be reversed with B12 injections and sometimes with B12 tablets (2).

Anaemia caused by a lack of vitamin B12 can result in symptoms which include:

• Extreme tiredness or fatigue

• A lack of energy or lethargy

• Being out of breath

• Feeling faint

• Headache

• Ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

• Lack of appetite

More specific symptoms linked to a lack of vitamin B12 include:

• Yellowing of the skin

• Sore, red tongue

• Mouth ulcers

• Changes or loss of some sense of touch

• Feeling less pain

• Walking problems

• Vision problems

• Mood changes, irritability, depression or psychosis

• Symptoms of dementia

Rarely, vitamin B12 deficiency can result in irreversible damage to the nervous system.

Over the last decade or so, researchers have strongly implicated the toxic amino acid homocysteine in a variety of disease states.

Homocysteine tends to accumulate in the body whenever vitamin B12 gets deficient, and this accumulation has been linked with increased risk of Alzheimer’s and other neuropsychiatric disease (3-5), cardiovascular disease (6,7) chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia (8) multiple sclerosis (9) and kidney disease (10), among other conditions.

Folic acid deficiency can also lead to increased homocysteine levels. This is because folate and vitamin B12, in their active ‘coenzyme’ forms, are both necessary cofactors for the enzymatic conversion of homocysteine to methionine.

Until recently it was thought that the availability of folate was the most important determinant of the body’s ability to re-methylate homocysteine.

New research has revealed that vitamin B12 is more important for homocysteine disposal than previously believed (9,11-13).

For example, a study conducted among dialysis patients with kidney failure showed that a monthly injection of vitamin B12 plus conventional oral folate was more effective than high-dose folate without vitamin B12 in lowering elevated homocysteine (11).

Where does vitamin B12 come from?

Vitamin B12 is synthesised only by certain bacteria, and is not made by either plants or animals.

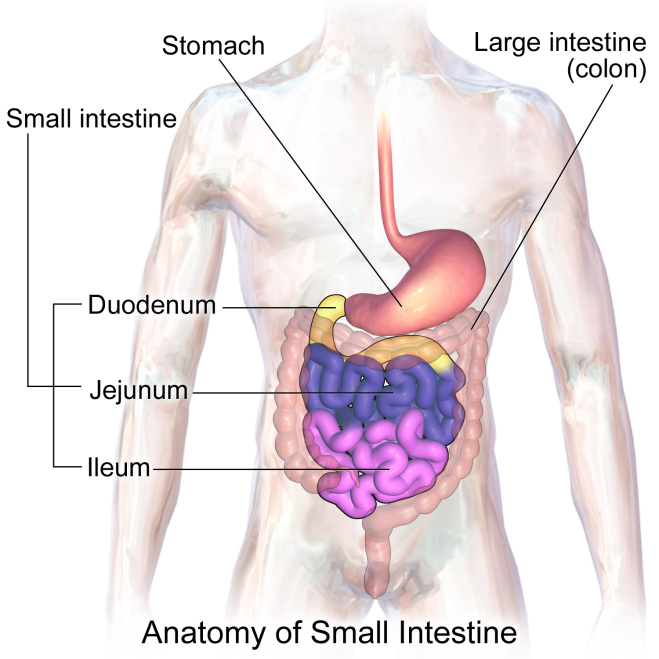

Ruminants, like cows, goats, sheep, giraffes, llamas, buffalo, and deer, are unique in that bacteria in their stomachs (rumen) synthesise vitamin B12, which then moves down and is absorbed by their small intestines.

Animal tissues store bacteria-synthesised vitamin B12, which can then be passed along the food chain by animals eating other animals (14).

The human gut also contains vitamin B12-synthesising bacteria, living from the mouth to the anus (15).

In humans, most intestinal vitamin B12 is produced in our large intestine, or colon, which is home to 4 trillion bacteria per cm3 of faeces.

Unfortunately, most vitamin B12 is absorbed in the small intestine, which is upstream of the large intestine, so the B12 produced in the latter is largely unavailable to us, unless we eat poop, which is obviously not recommended.

Faeces of cows, chickens and sheep also contain active vitamin B12.

In the past, people lived in close contact with farm animals. Animal manure was used to fertilise the land and people ate vegetables straight from the soil, so they would naturally have consumed small amounts of vitamin B12, even if they did not eat animal products.

Nowadays, most people have little or no contact with farm animals and consume vegetables which are industrially washed and disinfected before reaching supermarkets. In addition, our living environments are heavily sanitised.

These changes to human lifestyle, whilst beneficial in many respects, have likely led to a reduction in naturally occurring intake of vitamin B12.

Though it’s generally stated that people don’t benefit much from the synthesis of vitamin B12 in the human gut because most is made in the colon, there is evidence from healthy subjects that at least two groups of organisms in the small intestine, Pseudomonas and Klebsiella sp., may synthesise significant amounts of vitamin B12 which can be actively absorbed in the presence of intrinsic factor (16).

Foods derived from animals – meat, milk, eggs, fish and shellfish – are thus the major dietary sources of vitamin B12; the richest natural sources are liver and kidney.

Eating a diet rich in animal products will, however, give you a one-in-two chance of dying prematurely from a heart attack or stroke; a one-in-seven chance of breast cancer or a one-in-six chance of prostate cancer (17). Such a diet also results in obesity, diabetes, osteoporosis, constipation, indigestion, and arthritis (18).

So what can you do to avoid vitamin B12 deficiency if you don’t want to eat animals?

Vitamin B12 deficiency and plant-based diets

If you’re on a strict vegan diet – no meat, fish, dairy, or eggs – you have a low risk of vitamin B12 deficiency, which increases gradually with time, as body reserves of B12 are used up.

On average, for someone raised on the Western diet, about 2 to 5 milligrams of B12 are stored, mostly in the liver. It’s been calculated that most people have a 3 to 6 year reserve of this vital nutrient (19).

Conservation of B12 by the body boosts the time this supply lasts by 10-fold.

It’s estimated to take at least 20-30 years to deplete body reserves of vitamin B12, in the unlikely event of zero vitamin B12 intake during this period, as there are efficient mechanisms for re-absorbing and re-circulating B12 between the liver and intestines (20).

Vitamin B12 deficiency is more common in older people and affects around one in 10 over 75s (21).

Pregnant women on a strict vegan diet are also at a higher risk of B12 deficiency (22).

Blood levels of vitamin B12 can be measured directly and are a means to help diagnose deficiency.

Values above 150 pg/ml (picograms per millilitre) are considered normal, and levels below 80 pg/ml represent unequivocal B12 deficiency (23).

Absorption of vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 deficiency most commonly occurs due to health problems with the stomach and intestine, caused by autoimmune diseases, ulcers, parasites or surgery, rather than to a lack of B12 in the diet (24).

Vitamin B12 is the only nutrient that requires a cofactor for efficient absorption.

The cells of the stomach produce a substance, called intrinsic factor, which combines with vitamin B12 released from food, after acidic digestion in the stomach (25).

This intrinsic factor-B12 complex then travels to the end of the small intestine, called the ileum, where it’s actively absorbed.

If intrinsic factor isn’t produced due to damage to the parietal cells of the stomach, for example caused by pernicious anaemia, vitamin B12 cannot be absorbed and does not reach the cells where it’s needed.

Vitamin B12 can cross the intestine by passive absorption, but this mechanism does not use intrinsic factor; as a result, it’s 1000 times less efficient (26).

Plant-based sources of vitamin B12

As highlighted above, vitamin B12 is made only by certain bacteria and not by plants or animals.

Some plant-based foods have been shown to contain vitamin B12, due to their association with bacteria that synthesise it.

I’ve already mentioned that different forms of vitamin B12 exist, some of which are biologically inactive and are referred to as pseudovitamin B12.

When reviewing the scientific literature, it’s important to be clear if a food source contains active or inactive vitamin B12, as well as how reliable it is as a source of vitamin B12.

Consuming inactive or pseudovitamin B12 will not benefit your health in the slightest.

Growing vegetables in organic cow manure

Some reports in the literature suggest that adding an organic fertiliser such as cow manure significantly increases the vitamin B12 content of vegetables such as spinach leaves, i.e., approximately 0.14 μg per 100 g fresh weight (27).

This sounds potentially exciting but research indicates that most organic fertilisers, particularly those made from animal manures, contain considerable amounts of the inactive form – pseudovitamin B12 (28).

It’s also worth pointing out that you’d have to eat 3 lb (1.4 kg) of this organically grown spinach to obtain the guideline daily amount of vitamin B12.

Tempeh

A fermented soybean-based food called tempeh has been shown to contain a considerable amount of biologically active vitamin B12 (0.7–8.0 μg per 100 g) (29).

Tempeh originated in Indonesia and is made from whole soybeans, which are soaked, de-hulled, and partly cooked. They are then fermented for 24 to 36 hours at 30°C with the spores of a fungus, Rhizopus oligosporus or Rhizopus oryzae, forming a solid block meshed together with a white mycelium.

Different batches of tempeh may vary substantially in the amount of vitamin B12 they contain, so this is not necessarily a reliable source.

Cooked tempeh can be eaten alone, or used in chilli, stir fries, soups, salads, sandwiches, and stews. Tempeh’s complex flavour has been described as nutty, meaty, and mushroom-like. It freezes well, and is now commonly available in many western supermarkets, as well as in ethnic markets and health food stores.

Tea leaves

Vitamin B12 is also found in various types of tea leaves (approximately 0.1 to 1.2 μg vitamin B12 per 100 g dry weight) (30).

For example, vitamin B12-deficient rats were fed a Japanese fermented black tea (Batabata-cha) drink for 6 weeks, and their B12 deficiency was reduced compared with control rats (31).

Consumption of 1–2 litres of the fermented tea drink (typical regular consumption in Japan), which is equivalent to 20 to 40 ng of vitamin B12, is not however sufficient to meet the guideline daily intake of 2 μg per day for adult humans.

It’s important to note that Japanese teas such as Batabata-cha are made in a different way from the Indian black teas commonly consumed in Europe and the US, so the results are not applicable to tea-drinking in general.

You can buy Batabata-cha online.

Mushrooms

Mushrooms are fungi rather than plants. Various species of mushroom have been analysed for active vitamin B12 content.

Several wild edible mushroom species popular in Europe were found to contain zero or trace levels (approximately 0.09 μg per 100 g dry weight) of vitamin B12: porcini mushrooms (Boletus sp.), parasol mushrooms (Macrolepiota procera), oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), and black morels (Morchella conica).

In contrast, the fruiting bodies of black trumpet (Craterellus cornucopioides) and golden chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) contained higher levels of active vitamin B12 (1.09–2.65 μg per 100 g dry weight) (32).

High levels of active vitamin B12 were detected in the commercially available dried shiitake mushroom fruiting bodies (Lentinula edodes), with the average measured at approximately 5.61 μg per 100g dry weight (33).

Shiitake mushrooms can be added to soups and stir-fries, steamed, or sautéed with onions and other vegetables to create a wide variety of nutritious and delicious dishes.

Please click here for a recipe for mushroom stroganoff – a plant-based, vegan recipe using shiitake mushrooms and nutritional yeast, which contains 112 per cent of the recommended daily intake of vitamin B12 per serving.

Sea vegetables (seaweed)

Nori – the dried green and purple lavers commonly used to make sushi (Enteromorpha sp. and Porphyra sp., respectively) – contain substantial amounts of the biologically active form of vitamin B12 (approximately 63.6 μg per 100 g dry weight and 32.3 μg per 100 g dry weight, respectively) (34).

Please click here for a recipe for vegetable sushi nori.

A nutritional analysis of six vegan children who had consumed vegan diets including brown rice and dried purple laver (nori) for 4 to 10 years suggested that the regular consumption of nori may prevent vitamin B12 deficiency (35).

Other edible seaweeds contain zero or only trace levels of vitamin B12.

Foods fortified with vitamin B12

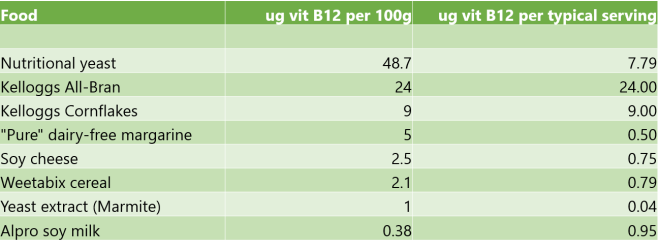

Vitamin B12 can be obtained from many everyday food items that are fortified, such as veggie burger and sausage mixes, yeast extracts, vegetables stocks, margarines, breakfast cereals and soya milks.

Many of these food products are heavily processed, so please read the labels to check what you’re consuming.

See the table below for a guide to how much vitamin B12 is contained in a range of these foods.

Vitamin B12 supplements

Vitamin B12 is found in almost all multivitamins, often referred to by its scientific name, cobalamin.

Dietary supplements that contain only vitamin B12, or vitamin B12 with nutrients such as folic acid and other B vitamins, are also available.

Vitamin B12 is also available in sublingual forms (which are dissolved under the tongue). There is no evidence that sublingual forms are better absorbed than pills that are swallowed.

A prescription form of vitamin B12 can be administered as an injection. This is usually used to treat vitamin B12 deficiency.

Vitamin B12 is also available as a prescription medication in nasal gel form (for use in the nose).

Forms of vitamin B12 in supplements

As a food additive and a supplement pill, vitamin B12 is usually found in the form cyanocobalamin, which is cobalamin bonded to a cyanide ligand.

Cyanocobalamin does not occur in nature, but is produced semi-synthetically from bacterial hydroxycobalamin and then used in many pharmaceuticals and supplements, and as a food additive, because of its stability and lower production cost.

Cyanocobalamin was originally produced by accident and at first remained unrecognised.

Historically, during the production process, activated charcoal columns were used to purify vitamin B12 synthesised by bacteria.

Cyanide is naturally present in activated charcoal, and hydroxycobalamin, which has great affinity for cyanide, picks it up, and is changed to cyanocobalamin.

Nowadays, industrial production of cyanocobalamin begins with fermentation of the bacteria Propionibacterium shermanii or Pseudomonas denitrificans; these strains make about 100 000 times more vitamin B12 than they need for their own growth (37,38).

This process yields a mixture of methyl-, hydroxy-, and adenosylcobalamin.

These compounds are converted to cyanocobalamin by addition of potassium cyanide in the presence of sodium nitrite and heat.

In the body, cyanocobalamin is converted to the human physiological forms methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin, leaving behind the cyanide, albeit in minimal concentration.

Is cyanocobalamin toxic?

On many natural health sites on the internet, you’ll come across warnings about the alleged toxicity of cyanocobalamin due to the production of cyanide during its metabolism.

Is this fact or fiction?

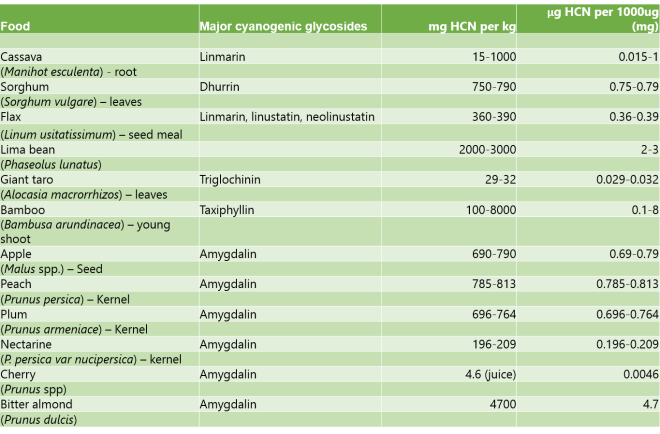

Cyanides can occur naturally or be man-made and it’s true that many are powerful and rapid-acting poisons.

Hydrogen cyanide (HCN), which is a gas, and the simple cyanide salts (sodium cyanide and potassium cyanide) are common examples of cyanide compounds.

Certain bacteria, fungi, and algae can produce cyanide, and cyanide is found naturally in a number of foods and in over 2650 plants (39-41).

In certain plant foods, including almonds, millet sprouts, lima beans, soy, spinach, bamboo shoots, and cassava roots (which are a major source of food in tropical countries), cyanides occur naturally as part of sugars and other compounds. The sugar-cyanide complexes are sometimes referred to as cyanogenic glycosides.

When the plant is damaged or chewed a chemical reaction occurs in the harmed cell and the cyanide is released as a natural defence.

The human body can detoxify a small amount of cyanide in the liver through a pathway involving a molecule called thiosulfate.

Researchers have estimated the rate of detoxification of cyanide in humans at between 1µg (micrograms) and 17µg per kg per minute in the absence of antidotes (42).

Poisoning occurs when there is not enough thiosulfate to neutralise all the cyanide.

At low toxic concentrations cyanide can provoke nausea, vomiting, general weakness and dizziness.

At lethal concentrations, cyanide inhibits cellular respiration, causing cardiac arrest and rapid death.

A lethal dose to humans is thought to be 98 mg (milligrams) in one day, with a lowest documented lethal dose of 37.8 mg (0.54mg/kg body weight) (43).

The amount of cyanide in 1000 µg (1000 micrograms or 1 milligram) of cyanocobalamin is 20 µg (micrograms), or 0.05 per cent of the lower level thought to be harmful.

To put this in context, the inhaled smoke from one cigarette contains 40 to 100 µg cyanide (44).

Plants contain between 0.01 to 5 µg hydrogen cyanide (HCN) per 1000 µg (mg) (39-41).

So if you ate, say, I tablespoon (10 g) of flax meal, you’d potentially consume 3600 µg HCN, which is obviously much more than the 2 µg cyanide from eating a 1000 µg cyanocobalmin pill.

The safety and effectiveness of the cyanocobalamin “cyanide complex” for treating neurologic problems has, however, been questioned; therefore, other forms, such as methylcobalamin and hydroxycobalamin are also used for the prevention and treatment of B12-related conditions (45).

Hydroxycobalamin is typically used in vitamin B12 injections but is reported to be less stable than cyanocobalamin.

Chemical stability studies show that, at worst, a solution of hydroxycobalamin in pH 4.3 acetate buffer will retain at least 90 per cent of claimed cobalamin at 30°C for 170 weeks (46).

If you’d prefer to avoid consuming even small amounts of cyanide every day, you can also buy liquid supplements for oral use containing hydroxycobalamin.

Existing evidence does not suggest any substantial differences among forms with respect to absorption or bioavailability.

Are ‘natural’ vitamin B12 supplements better?

High levels of vitamin B12 are described on the nutritional labels of dietary supplements that contain edible blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) such as Spirulina, Aphanizomenon, and Nostoc.

Although substantial amounts of vitamin B12 are detected in these commercially available supplements, lab studies show that these supplements often contain large amounts of pseudovitamin B12, which has no biological effect (47).

Chlorella tablets (eukaryotic microalgae Chlorella sp.) used in human food supplements contain biologically active vitamin B12 (48), however, contents vary substantially between commercially available Chlorella tablets (from zero to several hundred μg of vitamin B12 per 100 g dry weight), so these may be an unreliable source (33).

Can vitamin B12 supplements interact with medicines?

Vitamin B12 can interact or interfere with medicines that you take, and in some cases, medicines can lower vitamin B12 levels in the body.

Here are several examples of medicines that can interfere with the body’s absorption or use of vitamin B12:

• Chloramphenicol (Chloromycetin®), an antibiotic that is used to treat certain infections.

• Proton pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole (Prilosec®) and lansoprazole (Prevacid®), that are used to treat acid reflux and peptic ulcer disease.

• Histamine H2 receptor antagonists, such as cimetidine (Tagamet®), famotidine (Pepcid®), and ranitidine (Zantac®), that are used to treat peptic ulcer disease.

• Metformin, a drug used to treat diabetes.

You are advised to tell your doctor, pharmacist, and other health care providers about any dietary supplements and medicines you take. They can tell you if those dietary supplements might interact or interfere with your prescription or over-the-counter medicines or if the medicines might interfere with how your body absorbs, uses, or breaks down nutrients.

What dose of vitamin B12 supplement should I take?

As noted above, official dietary guidelines for intake of vitamin B12 are approximately 2 µg (micrograms) per day for adults and less than 1 µg per day for children.

Most vitamin B12 supplements sold contain 500 to 5000 µg (micrograms) per pill, which is between 250 and 2500 fold higher than the guideline dietary intake.

The body’s ability to absorb vitamin B12 from dietary supplements is largely limited by the capacity of intrinsic factor produced in the stomach.

Studies have shown that absorption of physiological doses of vitamin B12 is limited to approximately 1.5 to 2 µg per dose or meal, due to saturation of the active uptake system (49).

Regardless of dose, approximately 1 per cent of vitamin B12 is absorbed by passive diffusion and consequently this process becomes quantitatively important at high levels of exposure (50,51).

Bioavailability for those who need vitamin B12 the most is especially poor, because of weaknesses in their stomach and intestines, affecting either classical intrinsic factor-mediated absorption or passive B12 absorption.

In healthy subjects, bioavailability of cyanocobalamin has been shown to be approximately 5 per cent of the oral dose (52).

Evidence shows that many elderly persons respond poorly to daily oral doses under 500 µg, with bioavailability of 2 per cent or less (53,54).

Those least in need of vitamin B12 usually have normal absorption and are thus at greatest risk for whatever unknown adverse effects of high-dose supplementation or fortification might emerge, such as potential effects of excess accumulation of cyanocobalamin (55).

That said, in 2000 the European Union Scientific Committee on Food concluded that no adverse effects have been associated with excess vitamin B12 intake from food or supplements in healthy individuals, and that vitamin B12 has a history of safe long-term use as a therapeutic agent given in high dosages (56).

In vitamin B12 replacement therapy oral dosages between 1-5 mg (milligrams) vitamin B12 are used, with no supportive evidence of adverse effects (56).

From reviewing the literature, it appears that elderly people suffering from vitamin B12 deficiency are either given injections of 1000 µg once per day for 10 days (after 10 days, the dose is changed to once weekly for four weeks, followed by once monthly for life); or oral doses of 125 to 2,000 micrograms daily for up to 2.5 years or longer, to ensure adequate amounts are reaching the bloodstream.

Otherwise healthy meat or fish eaters are unlikely to need supplements at all.

For healthy people on strict vegan or plant-based diets, who are not consuming fortified foods or foods naturally containing vitamin B12, one 500 µg pill per week or 5µg of a liquid formulation per day is likely to be adequate (57).

If you’re concerned about your vitamin B12 levels, please go and consult your physician or qualified healthcare provider. They’ll be able to arrange for blood tests to check:

- whether you have a lower level of haemoglobin (a substance that transports oxygen) than normal

- whether your red blood cells are larger than normal

- the level of vitamin B12 in your blood

- the level of folate in your blood

These tests can often help identify people with a possible vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, but they are not necessarily conclusive, because some people can have problems with normal levels of these vitamins, and others can have low levels despite having no symptoms.

This means it is very difficult to devise definitive criteria for the diagnosis of vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, and this is why it is important for your symptoms to be taken into account when a diagnosis is made.

I hope this post has helped to answer any questions you may have had about vitamin B12 – if you have any others, please write in the comments below.

If you’ve enjoyed this post and would like to keep in touch please sign up for my free email newsletter and get a free report on calcium and your health.

You can also visit my website and follow me on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and LinkedIn.

References

1. Krautler B. Vitamin B12: chemistry and biochemistry. Biochemical Society transactions. 2005;33(Pt 4):806-810.

2. Butler CC, Vidal-Alaball J, Cannings-John R, et al. Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Family Practice. 2006;23(3):279-285.

3. McCaddon A DG, Hudson P, Tandy S, Cattell H. . Total serum homocysteine in senile dementia of Alzheimer type. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13(4):235-239.

4. Clarke R SA, Jobst KA, Refsum H, Sutton L, Ueland PM. . Folate, vitamin B12, and serum total homocysteine levels in confirmed Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1998;55(11):1449-1455.

5. Stanger O, Fowler B, Piertzik K, et al. Homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 in neuropsychiatric diseases: review and treatment recommendations. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2009;9(9):1393-1412.

6. Araki A SY, Ito H. . Plasma homocysteine concentrations in Japanese patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: effect of parenteral methylcobalamin treatment. Atherosclerosis. 1993;103(2):149-157.

7. Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: evidence on causality from a meta-analysis. Vol 3252002.

8. Regland B AM, Abrahamsson L, Bagby J, Dyrehag LE, Gottfries CG. . Increased concentrations of homocysteine in the cerebrospinal fluid in patients with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26(4):301-307.

9. Baig SM QG. Homocysteine and vitamin B12 in multiple sclerosis. Biogenic Amines. 1995;11(6):479-485.

10. Levi A, Cohen E, Levi M, Goldberg E, Garty M, Krause I. Elevated serum homocysteine is a predictor of accelerated decline in renal function and chronic kidney disease: A historical prospective study. European journal of internal medicine. 2014;25(10):951-955.

11. Hoffer LJ BI, Hongsprabhas P, Shrier I, Saboohi F, Davidman M, Bercovitch DD, Barre PE. A tale of two homocysteines–and two hemodialysis units. Metabolism. 2000;49(2):215-219.

12. D’Angelo A CA, Madonna P, Fermo I, Pagano A, Mazzola G, Galli L, Cerbone AM. The role of vitamin B12 in fasting hyperhomocysteinemia and its interaction with the homozygous C677T mutation of the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene. A case-control study of patients with early-onset thrombotic events. 2000;83(4):563-570.

13. Yajnik CS, Lubree HG, Thuse NV, et al. Oral vitamin B12 supplementation reduces plasma total homocysteine concentration in women in India. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition. 2007;16(1):103-109.

14. Watanabe F YY, Tanioka Y, Bito T. Biologically active vitamin B12 compounds in foods for preventing deficiency among vegetarians and elderly subjects. J Agric Food Chem. . 2013;61(28)(Jul 17):6769-6775.

15. Albert MJ MV, Baker SJ. . Vitamin B12 synthesis by human small intestinal bacteria. Nature. 1980;283(5749)(Feb 21):781-782.

16. Albert MJ, Mathan VI, Baker SJ. Vitamin B12 synthesis by human small intestinal bacteria. Nature. 1980;283(5749):781-782.

17. Campbell TC, Campbell TM. The China study : the most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted and the startling implications for diet, weight loss and long-term health. 1st BenBella Books ed. Dallas, Tex.: BenBella Books; 2005.

18. McDougall J. The Starch Solution. Rodale Press; 2013.

19. Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate OBV, and Choline. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Estimation of the Period Covered by Vitamin B12 Stores. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US);1998.

20. Schjonsby H. Gut. 1989;30:1686-1691.

21. Control CfDPa. Vitamin B12 Deficiency. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/b12/intro.html.

22. Black MM. Effects of vitamin B(12) and folate deficiency on brain development in children. Food and nutrition bulletin. 2008;29(2 Suppl):S126-131.

23. Stabler S AR. Vitamin B12 Deficiency As A Worldwide Problem. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2004;24:299-326.

24. Stabler SP. Vitamin B12 Deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(2):149-160.

25. Kozyraki R, Cases O. Vitamin B12 absorption: mammalian physiology and acquired and inherited disorders. Biochimie. 2013;95(5):1002-1007.

26. ARMSTRONG BK. Absorption of Vitamin B12 from the Human Colon. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 1968;21(4):298-299.

27. A. M. Enrichment of some B-vitamins in plants with application of organic fertilizers. Plant Soil. 1994;167:305-311.

28. Bito T. ON, Takenaka S., Yabuta Y., Miyamoto E., Nishihara E., Watanabe F. . Characterization of vitamin B12 compounds in biofertilizers containing purple photosynthetic bacteria. Trends Chromatogr. 2012;7:23-28.

29. Nout M.J.R. RFM. Recent developments in tempe research. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1990;69:609-633.

30. Kittaka-Katsura H WF, Nakano Y. Occurrence of vitamin B12 in green, blue, red, and black tea leaves. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2004;50 (6)(Dec):438-440.

31. Kittaka-Katsura H. ES, Watanabe F., Nakano Y. . Characterization of corrinoid compounds from a Japanese black tea (Batabata-cha) fermented by bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:909-911.

32. Watanabe F. SJ, Takenaka S., Miyamoto E., Ohishi N., Nelle E., Hochstrasser R., Yabuta Y. . Characterization of vitamin B12 compounds in the wild edible mushrooms black trumpet (Craterellus cornucopioides) and golden chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius). J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2012;58:438-441.

33. Watanabe F, Yabuta, Y., Bito, T., & Teng, F. Vitamin B12-Containing Plant Food Sources for Vegetarians. Nutrients. 2014;6(5):1861–1873.

34. Watanabe F. TS, Katsura H., Masumder S.A., Abe K., Tamura Y., Nakano Y. Dried green and purple lavers (nori) contain substantial amounts of biologically active vitamin B12 but less of dietary iodine relative to other edible seaweeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999;47:2341–2343.

35. H S. Serum vitamin B12 levels in young vegans who eat brown rice. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 1995;41(6):587-594.

36. Agency FS. McCance and Widdowsons the Composition of Food. 7th ed. London: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2014.

37. Spalla C GA, Garofano L, Ferni G. . Microbial production of vitamin B12. In: EJ V, ed. Biotechnology of vitamins, pigments and growth factors. New York: Elsevier Appl Science; 1989:257-284.

38. Kusel JP FY, Demain AL. . Betaine stimulation of vitamin B12 biosynthesis in Pseudomonas denitrificans may be mediated by an increase in activity of d-aminolaevulinic acid synthase. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:835-841.

39. Haque MR BJ. Total cyanide determination of plants and foods using the picrate and acid hydrolysis methods. Food chemistry. 2002;77(1):107-114.

40. Simeonova FP FL. Hydrogen cyanide and cyanides: Human health aspects. Geneva: World Health Organisation;2004.

41. Shragg TA AT, Fisher Jr CJ. Cyanide poisoning after bitter almond ingestion. Western Journal of Medicine. 1982;136(1):65-69.

42. Newhouse KaC, N. Toxicological review of hydrogen cyanide and cyanide salts. Washington DC: US Environmental Protection Agency;September 2010.

43. Safety) IIPoC. Hydrogen cyanide and cyanides: human health aspects. Geneva: World Health Organization;2004.

44. Fiskel J CC, and Eschenroeder A. . Exposure and risk assessment for cyanide. 1981.

45. AG. F. Hydroxocobalamin versus cyanocobalamin. J R Soc Med. 1996;89(11)(Nov):659.

46. Marcus AD, Stanley JL. Stability of the cobalamin moiety in buffered aqueous solutions of hydroxocobalamin. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1964;53(1):91-94.

47. Watanabe F KH, Takenaka S, Fujita T, Abe K, Tamura Y, Nakatsuka T, Nakano Y. Pseudovitamin B(12) is the predominant cobamide of an algal health food, spirulina tablets. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47(11):4736-4741.

48. Kittaka-Katsura H. FT, Watanabe F., Nakano Y. . Purification and characterization of a corrinoid-compound from chlorella tablets as an algal health food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:4994–4997.

49. Minerals EGoVa. Report on safe upper levels for vitamins and minerals. LondonMay 2003.

50. Scott JM. Bioavailability of vitamin B12. European journal of clinical nutrition. 1997;51 (Suppl. 1):S49-S53.

51. Baik HWaR, R.M. Vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly. Annual Review Nutrition. 1999;19:357-377.

52. Castelli MC, Wong DF, Friedman K, Riley MGI. Pharmacokinetics of Oral Cyanocobalamin Formulated With Sodium N-[8-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)amino]caprylate (SNAC): An Open-Label, Randomized, Single-Dose, Parallel-Group Study in Healthy Male Subjects. Clinical Therapeutics.33(7):934-945.

53. Eussen SJ dGL, Clarke R, et al. . Oral cyanocobalamin supplementation in older people with vitamin B12 deficiency: a dose-finding trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(10)(May 23):1167-1172.

54. Hill MH, Flatley JE, Barker ME, et al. A vitamin B-12 supplement of 500 mug/d for eight weeks does not normalize urinary methylmalonic acid or other biomarkers of vitamin B-12 status in elderly people with moderately poor vitamin B-12 status. The Journal of nutrition. 2013;143(2):142-147.

55. Carmel R. Efficacy and safety of fortification and supplementation with vitamin B12: biochemical and physiological effects. Food and nutrition bulletin. 2008;29(2 Suppl):S177-187.

56. 2000. SCoFSCoFNEoO. Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on the tolerable upper intake level of vitamin B12. 2000.

57. McDougall J. Vitamin B12 Deficiency—the Meat-eaters’ Last Stand. McDougall Newsletter. November 2007.

![Microsoft PowerPoint - Presentation1 (3) [Read-Only]](https://drjanephilpott.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/dna-methylation.jpg?w=660&h=465)